Merzouk Sider is an economist, activist and eco-builder based in the Bouriane region in southwest France. Having vast experience in the IT field, he is a former teacher of 3D industrial design which he later applied to building with natural materials. Merzouk is also a member of Initiative Chanvre, an international effort to develop and promote low-cost business models and tools applicable to the industrial hemp industries.

HempToday: Tell us about the path that got you into natural building.

Merzouk Sider: In the early ’80s I set up a company that worked in IT, both on software and hardware. My clients were professionals looking for a wide range of solutions for technical drawings — scanners, etc. Later I realized the lifespan of these solutions was about six years — and we were basically creating things that from the beginning were planned to be obsolete — falling into the broader global monomaniacal pattern.

So I decided to stop such a crazy and nonsensical business. Because of my background in industrial drawing, and with my experience in IT and software, I started to teach 3D industrial design in secondary school based on dedicated software. This was in the ‘90s, when I was still living in Paris. Then, just at the shift of the millenium, my wife and I bought a second home in in the southwest of France, in a little region called Bouriane, whose main village is Gourdon.

I am really fond of new experiences, new beginnings. So once again I got into something from the ground up when we started to use natural materials to refurbish our house, where we permanently relocated from Paris. After gaining some experience with these materials, we started a company based on natural building and renovation.

HT: Describe for us the arc of that startup.

MS: Through the first exciting years, we became fully involved in the rat race, running after turnover and more clients, using more and more bio-based materials but on a rather industrial scale. Then we realized we’d fallen into the trap of reviving some old skills and techniques — and that was good — but we were more or less joining in the same patterns as the egotistical transnational companies. And we were, in effect, replacing the work of certain craftsmen.

I learned at this time that even with the best of intentions, we the people, we the consumers — as long as we are addicted to certain global and mainstream trends, we are playing into the hands of a cynical and suicidal modern capitalism. Having said that, please keep in mind that I am not a Marxist; I am an entrepreneur.

HT: How did you extricate yourself from that trap you describe?

MS: We set up an organization called Cercleco with some self-builders, eco-builders, professional craftsmen and other individuals. The strategy became to promote local natural building materials and creative uses of them — locally. We started stimulating local demand and began to promote the idea of setting up a local supply chain for wood in building, then wood byproducts used as fuel mainly for collective heating. In the meantime we were sequestrating C02, stimulating the local economy and creating jobs. We took the resources from some neglected local forests and applied them to the comfort of our houses and the warmth of our lives.

HT: Can you give us another practical example of how this localized economy works?

MS: Take food supply. We started CSA, an organization that matches the supply of six farmers to demand from more than 100 local families — who are delivered staples such as vegetables, milk, cheese, meat, bread, etc. This is the kind of local value chain we’re creating. And we are already spreading out to develop similar new projects locally and regionally.

HT: Bring this down to broader economic terms.

MS: In the rising 21st Century, we begin to see a collaborative and distributed economic system rising as well. This is driven by the urgent need to shift from a crazy oil-based economy to a bio-based world. And one that puts man in balance with nature. We need an economic system that is well-balanced regarding social and environmental impacts.

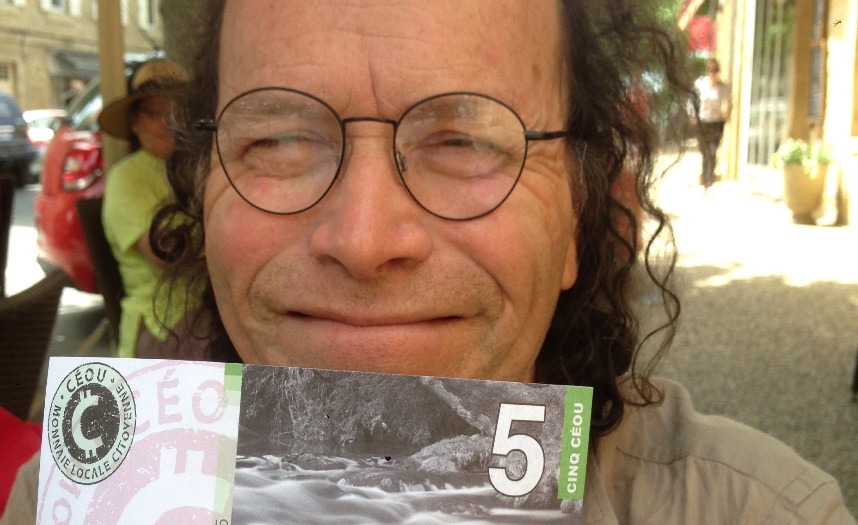

HT: Speaking of economic matters, what about this local currency, the Céou?

MS: As a key part of the distributed economic system, where value and products stay close to home, we needed a medium in order to facilitate the wide range of local exchanges. After months and months of learning from worldwide local experiences and experts, after months and months invested in brainstorming and talks, we launched the Céou, our local currency named in honor of our beloved river. We say the Céou should be like the water of the river after which it is named — it should flow and not be damned up by a happy few moneymen.

This is all a response to the dilemma of how to break away from the global economic system. But working local does not make sense without wide and exhaustive thinking. Let’s try to replace the reality of “globalization” with a distributed economy based on wide and exhaustive thinking. Beyond that, our local resilience must respond to our basics needs: eating and living are the first ones, then comes the exchange with our neighbors, in which we share love, conversation, ideas, help, care, goods and services.

HT: Is the Céou convertible.

MS: You can exchange it into Euros, but I don’t recommend it. Better to keep it out of the predators’ hands.

HT: How does hemp fit into all this?

MS: Quite naturally. It follows the pattern of local growing and production and local consumption. It’s true what most people emphasize and proselitize about — the thousands of uses for hemp byproducts, and the magic and mystical sides of the plant. This also fits into the distributed economic model. But we’re focused on hemp in building.

And we look further at the large number of other plants that have very interesting applications; flax for textiles, technical textiles, mulching; the myscanthus for biomass energy or reinforcement of composite wood, collective heating, and so on. All these plants were grown for thousands of years but then became exploited through the industrial revolutions of the 19th and 20th centuries. The linen industry has its routines and bourgeois; the wood industry has its traffickers and predators in all the forests of the world.

Anyway, I see hemp as one of the leading bio-resources to drive mankind to sustainability.

HT: Where do you see the hemp industries headed?

MS: Thanks mainly to the USA’s restrictions on hemp since the early 20th century, prohibition spread all around the world except in the former communist countries – the USSR and Central and Eastern European nations, plus France, Switzerland and China. That ban more or less killed the industry.

Now, considering the limited size of the global hemp market, the modern hemp industry has not achieved efficient and widely spread industrial tools. Concentrated industrial capital destined for the hemp markets has failed; the models that have been set out to revive the hemp business in the mainstream are not as profitable as expected. This failure limits the possibility for reviving hemp as a mainstream bio-resource. Old economic recipes can’t create something new; industrially concentrated capital and means have failed in the case of hemp.

Our local hemp business in Bouriane is a response to this, as is our participation in Initiative Chanvre, in which we’re a cell — a part of what can be a holistic and worldwide organism — a revolution; not the third industrial one, but the first distributed, bio-based and hope-based one.